The story of Rakhaldas Banerjee is as compelling as the ancient ruins he uncovered. Born into a wealthy family in Bengal in 1885, Banerjee's passion for history ignited at a young age among the medieval monuments of his hometown, Baharampur. His academic pursuits led him to join the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) in 1910, where he quickly ascended the ranks to become a superintending archaeologist.

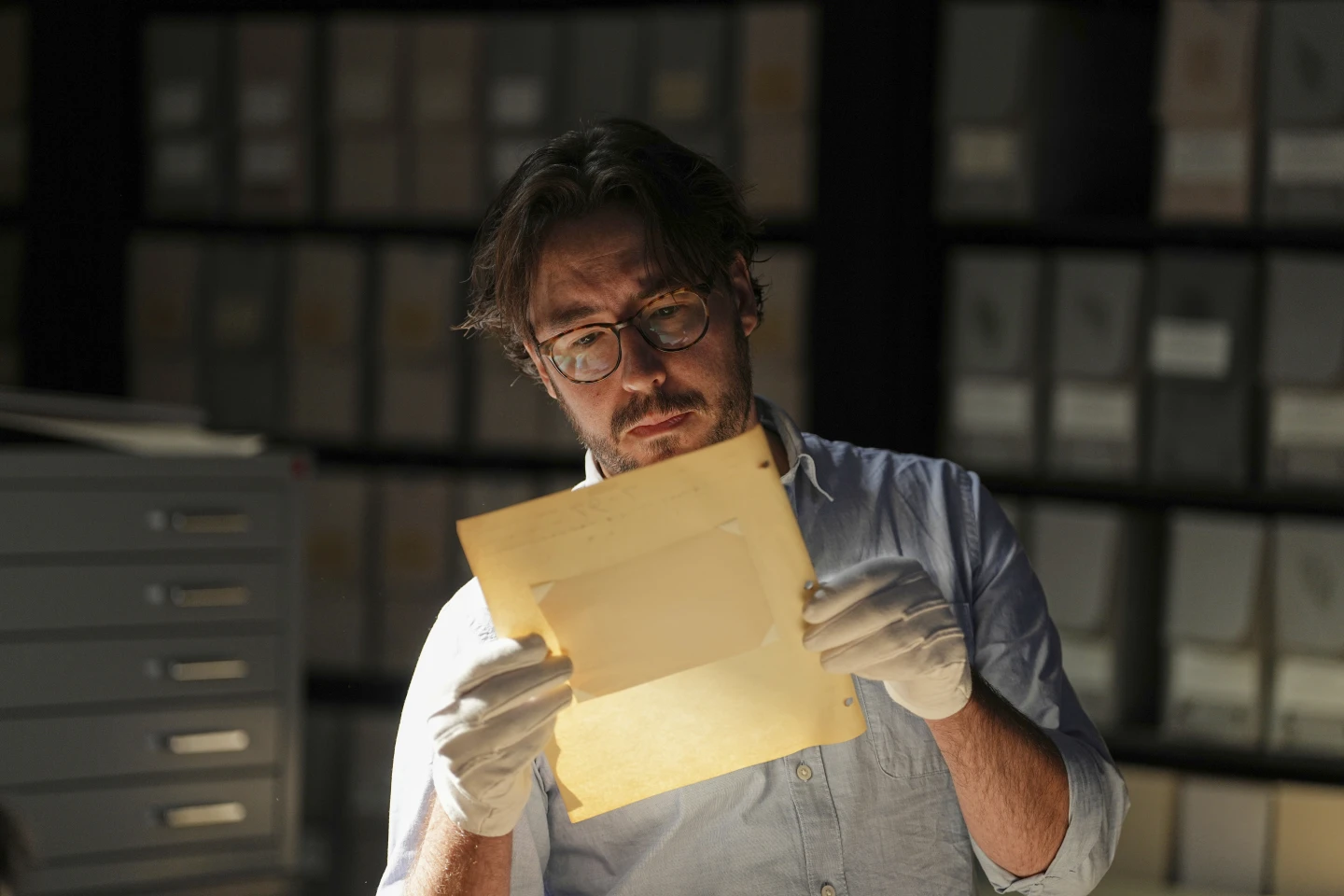

It was in 1919 that Banerjee first laid eyes on Mohenjo-daro, translating to "mound of the dead men" in Sindhi, located in present-day Pakistan. This site was the largest city of the thriving Indus Valley Civilization, which spanned an impressive geographical area from north-east Afghanistan to north-west India during the Bronze Age. Between 1922 and 1923, Banerjee's excavations unveiled layers of urban settlements, revealing insights into one of the earliest civilizations in history.

The discoveries made by Banerjee included ancient Buddhist stupas, coins, seals, and pottery. His findings, however, were mired in controversy, as many of his reports were allegedly suppressed and the ASI chief, John Marshall, took credit for the findings, obscuring Banerjee's crucial role. As noted by historians, Banerjee's bold and independent approach often clashed with the bureaucratic structures of the British colonial government, complicating his legacy.

Despite his groundbreaking work, Banerjee's career was marred by financial disputes and allegations of impropriety. He faced criticism for overspending on excavation-related expenses, leading to his transfer from the Mohenjo-daro site and his eventual resignation in 1927. Following his departure, he continued to work in academia, but his personal life was troubled by financial instability stemming from his extravagant lifestyle.

In a twist of fate, Banerjee found himself embroiled in a scandal involving the theft of a sacred idol. Though exonerated from these charges, his reputation suffered irreparable damage. Tragically, Banerjee passed away in 1930 at just 45 years of age, leaving behind a complicated but critical legacy in the field of archaeology.

Today, Rakhaldas Banerjee's contributions to the discovery and understanding of the Indus Valley Civilization serve as a powerful reminder of the often-unacknowledged figures in history who have significantly shaped our understanding of the past. His story reflects the persistent struggles of indigenous knowledge holders and historians seeking recognition and respect in a world that often overlooks their contributions.

It was in 1919 that Banerjee first laid eyes on Mohenjo-daro, translating to "mound of the dead men" in Sindhi, located in present-day Pakistan. This site was the largest city of the thriving Indus Valley Civilization, which spanned an impressive geographical area from north-east Afghanistan to north-west India during the Bronze Age. Between 1922 and 1923, Banerjee's excavations unveiled layers of urban settlements, revealing insights into one of the earliest civilizations in history.

The discoveries made by Banerjee included ancient Buddhist stupas, coins, seals, and pottery. His findings, however, were mired in controversy, as many of his reports were allegedly suppressed and the ASI chief, John Marshall, took credit for the findings, obscuring Banerjee's crucial role. As noted by historians, Banerjee's bold and independent approach often clashed with the bureaucratic structures of the British colonial government, complicating his legacy.

Despite his groundbreaking work, Banerjee's career was marred by financial disputes and allegations of impropriety. He faced criticism for overspending on excavation-related expenses, leading to his transfer from the Mohenjo-daro site and his eventual resignation in 1927. Following his departure, he continued to work in academia, but his personal life was troubled by financial instability stemming from his extravagant lifestyle.

In a twist of fate, Banerjee found himself embroiled in a scandal involving the theft of a sacred idol. Though exonerated from these charges, his reputation suffered irreparable damage. Tragically, Banerjee passed away in 1930 at just 45 years of age, leaving behind a complicated but critical legacy in the field of archaeology.

Today, Rakhaldas Banerjee's contributions to the discovery and understanding of the Indus Valley Civilization serve as a powerful reminder of the often-unacknowledged figures in history who have significantly shaped our understanding of the past. His story reflects the persistent struggles of indigenous knowledge holders and historians seeking recognition and respect in a world that often overlooks their contributions.