Artist Stary Mwaba is addressing the grave issue of Zambia's mining waste—specifically the towering heaps known as the "black mountains"—through his latest exhibit at the Lusaka National Museum. This work brings a deeply personal perspective to a haunting landscape that symbolizes years of environmental degradation and human struggle.

Reflecting on his childhood, Mwaba recalls how the black mountains, which housed toxic mining waste, were considered dangerous playgrounds. "As kids, we used to call it 'mu danger'—meaning 'in the danger'. It was a place we were drawn to even though we weren't meant to be there,” he explains. This nostalgia contrasts starkly with the current reality where young locals venture into these sites, not for fun, but in search of valuable copper ore, often risking their lives in the process.

Through his art, Mwaba highlights the plight of these young miners, who often work under criminalized circumstances for gang masters known as "jerabos." This precarious situation is exacerbated by soaring youth unemployment rates that hover around 45%. Mwaba’s compelling portraits portray these miners and their surroundings, crafted from repurposed newspaper articles, which he positions as "grand narratives." These captivating depictions capture the essence of life in the Wusakile neighborhood, ensconced in the shadows of the black mountains.

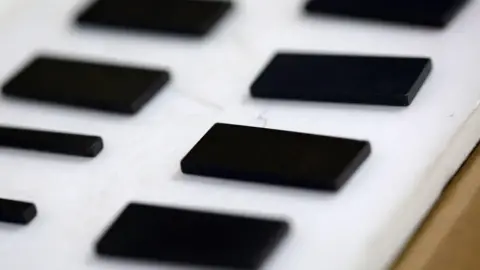

His innovative technique involves layering newspaper clippings, burning elements away to create holes, and blending in vibrant paints—creating what he describes as “little narratives” that echo the personal stories overshadowed by larger societal issues. “I take these grand narratives, and I create holes so that you can't make sense of the stories anymore," he notes. Each artwork conveys not just hardship, but also resilience, as seen in a portrait titled "Jerabo," which depicts a miner carefully preparing for the risks of his daily work.

While Mwaba's artistic progression stems from a familial background in mining, it evolved from a pivotal moment in 2011 when he assisted his daughter with a science project that stirred his awareness of environmental challenges related to mining—issues that resonate alarmingly in the present day. His compelling piece, "Chinese Cabbage," exposed the exploitative dynamics of Chinese mining firms in Zambia and brought him international acclaim.

Mwaba's efforts to document these experiences through art are deeply rooted in his connections to the communities affected by mining. He runs workshops that capture their stories and aspirations, significantly influencing transformative conversations around the vulnerable practices surrounding mining operations. “The worst thing that happened is when the black mountain was super-profitable, most of these young people quit school,” he reflects, highlighting a tragedy of lost futures.

Mwaba's powerful portrayals, such as “Boss for a Day”—which illustrates dreams and struggles in striking poses—demonstrate his dedication to giving a voice to those who feel disenfranchised. One impactful instance from a workshop involves a jerabo who recognized the dangers of this life and encouraged his younger brother to engage in the arts instead.

Through Mwaba’s lens, the toxic legacy of Zambia’s mining industry becomes more than just a backdrop; it emerges as a catalyst for advocacy, healing, and hope. His work encapsulates how art can serve as a poignant reminder of the fight for dignity and survival amidst adversity, bringing the narratives of marginalized communities into stark relief against the backdrop of Zambia’s rich mineral wealth.