NEW TOWN, N.D. — On a recent chilly fall morning, Ruth De La Cruz walked through the Four Sisters Garden, searching for Hidatsa squash. To college students in her food sovereignty program, the crop might simply be part of their curriculum. But for De La Cruz, it represents the lifework of her ancestors.

There’s some of the squash, yay, De La Cruz exclaimed upon discovering the small, pumpkin-like gourds basking in the morning sun. The garden is named after the Hidatsa tradition of planting squash, corn, sunflowers, and beans — the four sisters — together, as an illustration of agricultural practices deeply rooted in Indigenous culture.

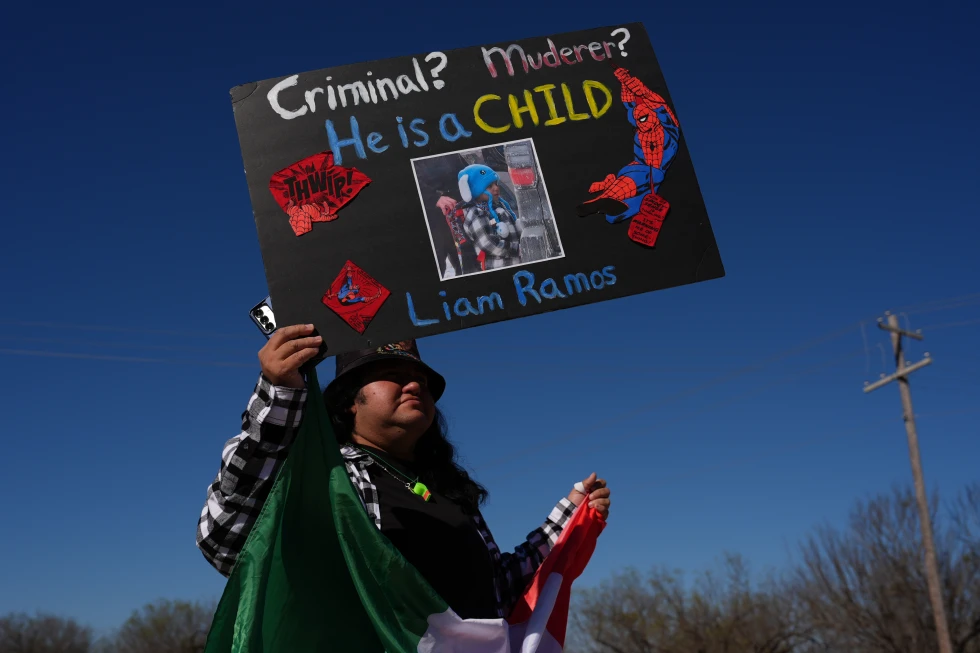

The college is part of the Mandan Hidatsa Arikara Nation and stands among over three dozen tribal colleges and universities across the country that faced funding cuts proposed earlier this year. Indigenous communities are bearing the brunt of fallout from federal budget reductions and the longest government shutdown in U.S. history. While an increase in funding for tribal colleges was recently announced, many college leaders continue to express apprehension over the future financial commitments from the government, which they view as critical for ensuring the continuity of Indigenous knowledge for generations to come.

This is not just a haven for access to higher education, but also a place where you get that level of culturally, tribally specific education, De La Cruz said, extolling the importance of contextual learning.

The U.S. government historically disrupted the passage of Indigenous knowledge and lifeways, yet promised through treaties and legislation to uphold the education and well-being of Indigenous peoples. These commitments, referred to as trust responsibilities, must be honored, according to Twyla Baker, the college’s president.

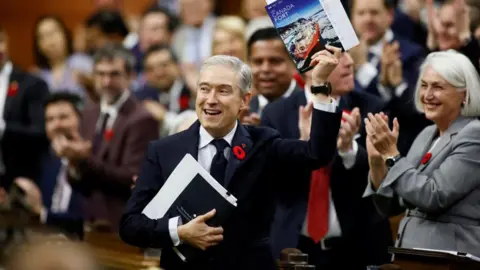

Despite a welcome 100% increase in funding announced by the U.S. Department of Education, challenges persist. This uptick in resources comes amidst cuts to other federal supports essential for tribal colleges, sparking concerns among advocates that the current funding model is precarious.

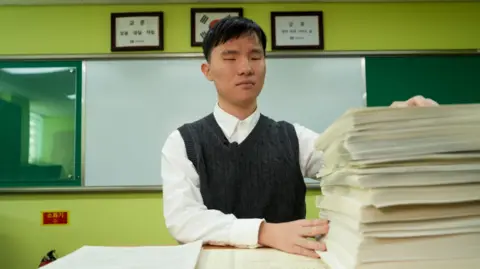

The significance of education extends beyond classroom experiences; it serves as a crucial means of preserving traditions threatened by systematic attempts of cultural erasure. As students like Zaysha Grinnell embrace their heritage through courses on Native languages and customs, they engage in a vital reclamation of identity.

You can’t get that anywhere else, Grinnell shared, emphasizing the unique and personal education offered at the college.

With the responsibility of carrying forward ancestral knowledge, the work happening at tribal colleges represents more than education; it stands as a vital effort in cultural preservation in a landscape marked by broken treaties and historical injustices.

There’s some of the squash, yay, De La Cruz exclaimed upon discovering the small, pumpkin-like gourds basking in the morning sun. The garden is named after the Hidatsa tradition of planting squash, corn, sunflowers, and beans — the four sisters — together, as an illustration of agricultural practices deeply rooted in Indigenous culture.

The college is part of the Mandan Hidatsa Arikara Nation and stands among over three dozen tribal colleges and universities across the country that faced funding cuts proposed earlier this year. Indigenous communities are bearing the brunt of fallout from federal budget reductions and the longest government shutdown in U.S. history. While an increase in funding for tribal colleges was recently announced, many college leaders continue to express apprehension over the future financial commitments from the government, which they view as critical for ensuring the continuity of Indigenous knowledge for generations to come.

This is not just a haven for access to higher education, but also a place where you get that level of culturally, tribally specific education, De La Cruz said, extolling the importance of contextual learning.

The U.S. government historically disrupted the passage of Indigenous knowledge and lifeways, yet promised through treaties and legislation to uphold the education and well-being of Indigenous peoples. These commitments, referred to as trust responsibilities, must be honored, according to Twyla Baker, the college’s president.

Despite a welcome 100% increase in funding announced by the U.S. Department of Education, challenges persist. This uptick in resources comes amidst cuts to other federal supports essential for tribal colleges, sparking concerns among advocates that the current funding model is precarious.

The significance of education extends beyond classroom experiences; it serves as a crucial means of preserving traditions threatened by systematic attempts of cultural erasure. As students like Zaysha Grinnell embrace their heritage through courses on Native languages and customs, they engage in a vital reclamation of identity.

You can’t get that anywhere else, Grinnell shared, emphasizing the unique and personal education offered at the college.

With the responsibility of carrying forward ancestral knowledge, the work happening at tribal colleges represents more than education; it stands as a vital effort in cultural preservation in a landscape marked by broken treaties and historical injustices.