Razanasoa Edmondine still looks shell-shocked as she recalls the death of her one-month-old grandson, killed by police tear gas in protests that have rocked Madagascar over the last two weeks.

It was just a normal Friday. My daughter-in-law was going to the market with the baby when they encountered demonstrators on the road, she tells the BBC at the family's home on the northern outskirts of the capital, Antananarivo.

Not long after, police showed up and started dispersing the protest with tear gas.

It was the second day of youth-led protests, triggered by anger over persistent power and water shortages, and Ms Edmondine's daughter-in-law ran into a nearby building with other protesters to take cover.

Police then fired more tear gas canisters into the building, quickly filling it with choking smoke.

With the streets in chaos, they could not get to a hospital until the following day. By then, the damage had been done.

The baby was trying to cry but no sound came out, says Ms Edmondine softly.

It was like something was blocking his chest. The doctor told us he had inhaled too much smoke. A couple of days later, he passed away.

Her grandchild is one of at least 22 people the UN says were killed during clashes between police and demonstrators in the early days of the protests, which have since escalated into broader dissatisfaction over corruption, high unemployment, and the cost-of-living crisis in one of the world's poorest nations.

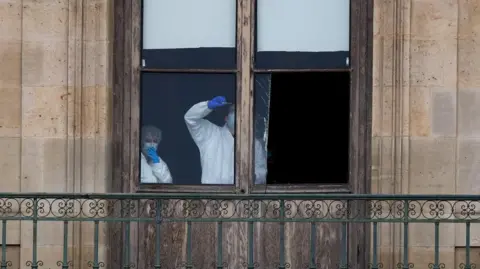

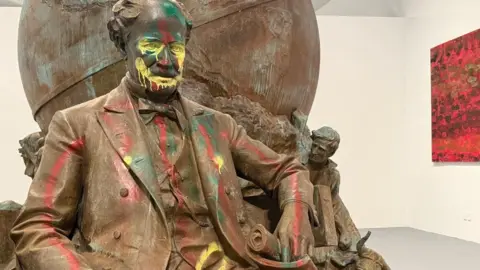

The government of President Andry Rajoelina has dismissed this figure as misinformation but has not provided its own numbers. However, it has emphasized that the value of property damage exceeds $47m (£35m). The first days of the protests were marked by widespread violence, with cars set on fire, shop windows smashed, and a two-month-old, multi-million-dollar cable car station vandalized.

As police launched tear gas, panic spread fast and people fled in every direction, seeking shelter inside any open building. Rabe, who only gave the BBC his first name, has accused the police of firing live bullets at peaceful protesters—a few blocks away from where Ms Edmondine's daughter-in-law was hiding.

He believes his son was shot from the front, as the bullet left a large open wound in his back—the likely exit wound.

Responding to accusations of police brutality, earlier this week President Rajoelina said, There have been deaths, we completely agree. And I truly sympathize with the suffering and pain of the families who have lost loved ones. But I want to tell you that these deaths are not protesters, they are not students. They are rioters. They are the ones who looted.

The anger of the youth movement behind the demonstrations, known as Gen Z Mada, has grown with the protesters now calling for the president to step down.

The evidence of young people's frustrations, whether it is unemployment, water scarcity or struggling businesses, is not hard to find across Antananarivo. At the airport, for example, visitors with just a few bags are quickly surrounded by two or three young people eager to help in exchange for a small tip.

One of the main protest organisers, who requested anonymity for safety reasons, told the BBC he had to walk a mile each day to get water from a well—and he considers himself middle-class.

President Rajoelina has asked the Malagasy people to give him one year to fix the problems driving the protests, saying he will resign if he fails to meet the deadline. But the complexities driving Madagascar deeper into poverty may require more than mere promises to resolve.