Recent developments in Brazil's legal landscape could pose grave risks to the Amazon rainforest, according to Astrid Puentes Riaño, a UN special rapporteur. This assessment follows the passage of a controversial law intended to expedite approvals for various development projects, including roads, dams, and mining operations. Critics label the legislation the "devastation bill," asserting that it could lead to severe environmental degradation and human rights infringements just as Brazil gears up to host the COP30 climate summit.

The new legislation, which has passed through lawmakers but awaits presidential approval, aims to streamline the complex process companies face in securing environmental licenses. Under these changes, developers may soon be able to self-declare their environmental impact for smaller projects through a simplified online form. Proponents argue that this could eliminate bureaucratic hurdles, while critics, including Riaño, caution that it undermines crucial environmental assessments.

Riaño highlighted concerns that the relaxed regulations could particularly impact the Amazon region, potentially allowing for mining and infrastructure projects to proceed without thorough evaluations. She pointed out that automatic renewals of existing licenses could further exacerbate deforestation as projects could proceed without comprehensive impact assessments.

This legislative push comes amidst alarming data revealing that significant areas of the Amazon were destroyed in 2024, exacerbated by forest fires and drought conditions linked to climate change. Environmental agencies now face a timeline of 12 months, extendable to 24, to make licensing decisions, with implications that missed deadlines could result in automatic approvals, thus raising further alarm among environmentalists.

While supporters claim the law will provide economic growth and the necessary infrastructure for renewable energy projects, opponents fear it could lead to catastrophic environmental disasters and violations of indigenous rights. Enhanced participation for indigenous and traditional communities is also at risk, as the bill relaxes the requirement for consultations unless communities are directly impacted.

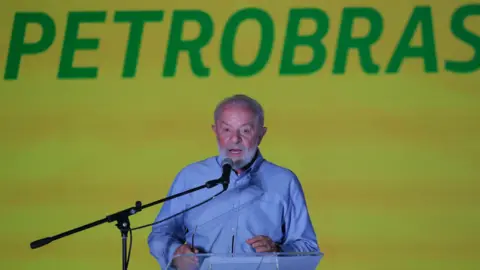

With the bill's fate resting in the hands of President Lula da Silva, fierce opposition has emerged, particularly from Brazil's Environment and Climate Change Minister, Marina Silva, who has condemned the bill. Even if the president vetoes the legislation, the conservative congress may still seek to overturn such a decision.

Brazil's Climate Observatory has labeled the bill as the most significant environmental setback since the military dictatorship era, a time notorious for deforestation and displacement of indigenous populations. Riaño asserts that if enacted, the law could lift protections over an area equal to 18 million hectares, potentially leading to devastating consequences for the Amazon and its inhabitants.

The new legislation, which has passed through lawmakers but awaits presidential approval, aims to streamline the complex process companies face in securing environmental licenses. Under these changes, developers may soon be able to self-declare their environmental impact for smaller projects through a simplified online form. Proponents argue that this could eliminate bureaucratic hurdles, while critics, including Riaño, caution that it undermines crucial environmental assessments.

Riaño highlighted concerns that the relaxed regulations could particularly impact the Amazon region, potentially allowing for mining and infrastructure projects to proceed without thorough evaluations. She pointed out that automatic renewals of existing licenses could further exacerbate deforestation as projects could proceed without comprehensive impact assessments.

This legislative push comes amidst alarming data revealing that significant areas of the Amazon were destroyed in 2024, exacerbated by forest fires and drought conditions linked to climate change. Environmental agencies now face a timeline of 12 months, extendable to 24, to make licensing decisions, with implications that missed deadlines could result in automatic approvals, thus raising further alarm among environmentalists.

While supporters claim the law will provide economic growth and the necessary infrastructure for renewable energy projects, opponents fear it could lead to catastrophic environmental disasters and violations of indigenous rights. Enhanced participation for indigenous and traditional communities is also at risk, as the bill relaxes the requirement for consultations unless communities are directly impacted.

With the bill's fate resting in the hands of President Lula da Silva, fierce opposition has emerged, particularly from Brazil's Environment and Climate Change Minister, Marina Silva, who has condemned the bill. Even if the president vetoes the legislation, the conservative congress may still seek to overturn such a decision.

Brazil's Climate Observatory has labeled the bill as the most significant environmental setback since the military dictatorship era, a time notorious for deforestation and displacement of indigenous populations. Riaño asserts that if enacted, the law could lift protections over an area equal to 18 million hectares, potentially leading to devastating consequences for the Amazon and its inhabitants.