When Stephen Scheeler became Facebook's Australia chief in the early 2010s, he was a true believer in the power of the internet, and social media, for public good.

It would herald a new era of global connection and democratise learning. It would let users build their own public squares without the traditional gatekeepers.

There was that heady optimism phase when I first joined and I think a lot of the world shared that, he told the BBC.

But by the time he left the firm in 2017, seeds of doubt about its work had been planted, and they've since bloomed.

There's lots of good things about these platforms, but there's just too much bad stuff, he surmises.

That's no longer an uncommon view as scrutiny of the largest social media companies has increased around the globe. A lot of it has centred on teenagers, who have emerged as a lucrative market for incredibly wealthy global firms - at the expense of their mental health and wellbeing, according to critics.

Various governments, from the state of Utah to the European Union, have been experimenting with limiting children's use of social media. But the most radical step so far is set to unfold in Australia – a ban for under-16s that has left tech companies scrambling.

Many of the social media firms affected have spent a year loudly protesting the new law, which requires them to take reasonable steps to keep underage users from having accounts on their platforms.

They have claimed this ban actually risks making children less safe, argued it impinges on their rights, and repeatedly pointed to the questions around the tech that will be used to enforce the policy.

Australia is engaged in blanket censorship that will make its youth less informed, less connected, and less equipped to navigate the spaces they will be expected to understand as adults, said Paul Taske from NetChoice, a trade group representing several big tech companies.

The worry inside the industry is that Australia's ban - the first of its kind - may inspire other countries.

It could become a proof of concept that gains traction around the world, says Nate Fast, a professor at the University of Southern California's Marshall School of Business.

In recent years, multiple whistleblowers and lawsuits have claimed that social media firms are prioritising profits over user safety.

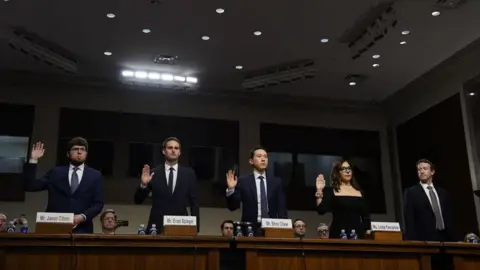

In January, a landmark trial will begin in the US hearing allegations that several – including Meta, TikTok, Snapchat and YouTube – have designed their apps to be addictive and knowingly covered up the harm their platforms cause. All deny this, but Meta founder Mark Zuckerberg and Snap boss Evan Spiegel have been ordered to testify in person.

In another ongoing case, state prosecutors alleged that Zuckerberg personally scuttled efforts to improve the wellbeing of teens on the company's platforms, including vetoing a proposal to ditch Instagram face-altering beauty filters which experts say fuel body dysmorphia and eating disorders.

Privately, many tech companies sought to influence the Australian government's approach to the ban, arguing that they should not bear the weight of responsibility for age verification on their platforms, as the technology to implement such measures is still fraught with issues.

As the social media ban looms, major platforms are beginning to unveil alterations to their services purportedly aimed at protecting younger users, yet critics argue these changes are merely reactive and insufficient in addressing the broader concerns surrounding youth safety.

It remains to be seen whether Australia’s approach will indeed result in a safer environment for children online or whether it will simply act as a catalyst for larger regulatory frameworks around the world.