Nine years after imposing a statewide alcohol ban to curb addiction, domestic violence, and financial ruin among its poorest families, Bihar - India's poorest state - still struggles to gauge the policy's effectiveness.

The gaps in implementation became glaring as the BBC shadowed Bihar officials in a misty October morning raid on bootleggers.

Armed excise officers, with a sniffer dog, sped across the Ganges on a boat to raid an illegal distillery.

On reaching the outskirts of the capital, Patna, the team found a ramshackle setup of a dozen metal drums - part of a makeshift apparatus fermenting jaggery, a type of cane sugar, into country liquor.

Vapour rose from the drums embedded in the riverside mud, the surfaces still warm.

The officers said the site was active minutes earlier, but the alcohol-makers had fled by the time they arrived.

They often get tipped off before a raid, an officer who didn't wish to be named said.

Despite these enforcement gaps, alcohol prohibition remains firmly in place in Bihar.

Passed in 2016 by Chief Minister Nitish Kumar after persistent demands from women's groups, the law was among the factors that helped his Janata Dal (United) - Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) alliance clinch a decisive state election victory earlier this month.

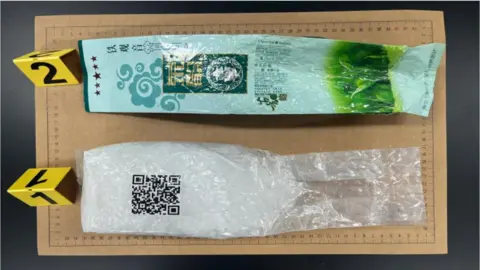

State officials tout the policy's success by pointing to big numbers: since the law took effect, 1.1 million cases have been registered and 650,000 people convicted for violations. But the devil lies in the detail.

More than 99% of these convictions are for consumption, rather than production, selling, or transport of illicit liquor. Moreover, alcohol remains widely available in the black market in Bihar.

In the six weeks leading to the recently held election, illicit alcohol worth more than 522 million rupees ($6.26 million, £4.96 million) was seized from across the state.

So why has Bihar been unable to enforce its ban more effectively?

Local police, who did not want to come on record, say it is a combination of several factors - including staff shortages, increasingly sophisticated smuggling methods and possible collusion between liquor makers and authorities.

There are laws that prescribe life imprisonment or even the death penalty for murder. But does that stop people from committing murder? No, it doesn't, said Ratnesh Sada, an outgoing minister whose department handled prohibition issues.

Mr Sada, however, insisted that action has been taken against at least a hundred individuals engaged in illegal alcohol trade, with their properties seized.

We destroy these setups, but within days they are up and running again, said Sunil Kumar, an excise official.

Bihar's geography makes enforcement even harder. The landlocked state borders Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, and West Bengal - all of which allow alcohol and serve as major sources of smuggled liquor. It also shares a 726km (449 mile), largely porous border with Nepal, which officials say has become a key conduit for alcohol smuggling, further complicating enforcement.

Despite the challenges, many women in Bihar - who still carry deep scars from their husbands' alcohol abuse - want the ban to continue.

In Chhapra district, Lalmunni Devi, who lost her husband after he consumed toxic liquor in 2022, said her life had been upended by alcohol abuse.

I just hope no one else has to suffer the same fate, she said.

Neetu Devi, another widow, broke down as she recalled her husband's death.

If the government were to shut down all such factories entirely, it [liquor] would no longer be available. It continues to be produced, and that's why people keep consuming it, she said.

Rajeev Kamal Kumar, an anthropologist at Patna's AN Sinha Institute of Social Sciences, who worked on a government study of prohibition, says both sides of the story are true.

Many women and elders say prohibition has improved household finances, children's education, and nutrition. But it is undeniable that illegal trade continues, he said.

Bihar is neither the first nor the only Indian state to impose prohibition; several others have tried it over the years. But such measures often trigger unintended consequences - from thriving black markets and deaths from illicit brews, to enforcement challenges that drain state resources.

The financial cost has also been considerable, as alcohol taxes remain a key source of revenue for many state governments.

Gujarat and Nagaland have had bans since 1960 and 1989, yet both still grapple with bootlegging.

Mizoram imposed prohibition in 1997, lifted it in 2015, reinstated it in 2019, and then relaxed it again in 2022 to allow the manufacture, sale, and export of wine made from local grapes.

Some other states have rolled back prohibition after encountering economic and administrative challenges.

For now, with the outgoing government slated to return to power, prohibition will remain in Bihar. But the policy remains a paradox - hailed as a social reform by some, criticized as ineffective by others.

Whether it has succeeded or merely shifted the problem underground is a question that continues to haunt the state.