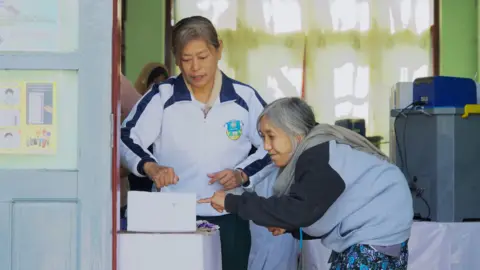

Fresh trauma arrives with every election season in Tanzania for 42-year-old Mariam Staford. For most, the fiesta-like rallies and songs, along with the campaign messages, signal a chance for people to make their voice heard. But for those with albinism, they bring terror. The first thing that comes to me is fear, Mariam tells the BBC as people prepare to vote for a president and parliament on Wednesday. I know that killings of people with albinism happen especially at election time in Tanzania, when witchcraft beliefs intensify. That's why I don't take part in campaigns… I am so afraid.

Albinism, which affects an estimated 30,000 people in Tanzania, is a rare genetic condition that reduces melanin - the pigment that gives colour to skin, eyes, and hair. Superstition has made those with the condition targets. The false belief that body parts of people with albinism bring wealth, luck, or political success has driven attacks and killings across Tanzania. Activists say such assaults intensify in the run-up to an election as people vie for political influence.

Mariam knows what this danger looks and feels like personally. In 2008, one of the bloodiest years for people with albinism in Tanzania as preparations for local elections were under way, machete-wielding men stormed into her bedroom in Kagera. They came at a late hour of the night, cut off my right hand [from above the elbow] and took it away, and then they also cut off my left hand.

Against the odds, Mariam survived; but she was five months pregnant and her unborn child did not. The attack forced her to abandon Kagera, one of the epicentres of ritualistic killings of people with albinism at the time. Now resettled in Kilimanjaro region, where a rights group for people with albinism built her a house and trained her in knitting, she makes sweaters. Yet the trauma remains.

Even now, Mariam relives the attack. When I wake up, I touch my arms and remember they are not there. It is something I will never escape. Despite government crackdowns and awareness raises, fears linger as recent attacks continue, underscoring an ongoing struggle for safety and recognition within the community. As the election approaches, Mariam chooses not to vote, opting instead for a quiet day at home. I don't think it will change anything in my life, she reflects.

Albinism, which affects an estimated 30,000 people in Tanzania, is a rare genetic condition that reduces melanin - the pigment that gives colour to skin, eyes, and hair. Superstition has made those with the condition targets. The false belief that body parts of people with albinism bring wealth, luck, or political success has driven attacks and killings across Tanzania. Activists say such assaults intensify in the run-up to an election as people vie for political influence.

Mariam knows what this danger looks and feels like personally. In 2008, one of the bloodiest years for people with albinism in Tanzania as preparations for local elections were under way, machete-wielding men stormed into her bedroom in Kagera. They came at a late hour of the night, cut off my right hand [from above the elbow] and took it away, and then they also cut off my left hand.

Against the odds, Mariam survived; but she was five months pregnant and her unborn child did not. The attack forced her to abandon Kagera, one of the epicentres of ritualistic killings of people with albinism at the time. Now resettled in Kilimanjaro region, where a rights group for people with albinism built her a house and trained her in knitting, she makes sweaters. Yet the trauma remains.

Even now, Mariam relives the attack. When I wake up, I touch my arms and remember they are not there. It is something I will never escape. Despite government crackdowns and awareness raises, fears linger as recent attacks continue, underscoring an ongoing struggle for safety and recognition within the community. As the election approaches, Mariam chooses not to vote, opting instead for a quiet day at home. I don't think it will change anything in my life, she reflects.