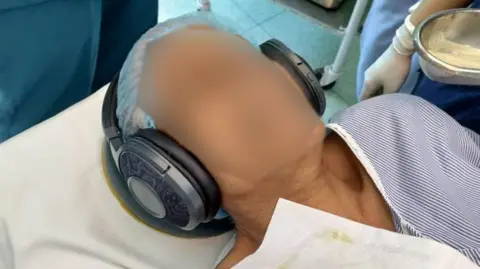

Under the bright lights of a Delhi operating theatre, a woman lies still as surgeons work to remove her gallbladder. Though she is under general anesthesia, the gentle notes of flute music fill the room, a melody enhancing her surgical experience. This quiet revolution in the operating theatre emerges from a new, peer-reviewed study conducted by researchers from Delhi's Maulana Azad Medical College and Lok Nayak Hospital, which reveals that music can reduce the dosage of anesthetic drugs needed, leading to quicker recovery times for patients.

The study showed that when patients listened to calming instrumental music during laparoscopic cholecystectomy procedures, they required less propofol and fentanyl compared to those who did not receive musical treatment. Not only did this facilitate a faster return to consciousness, but it also contributed to lower stress hormone levels during surgery, enabling a smoother recovery process.

Dr. Farah Husain, a senior anaesthesia specialist involved in the research, emphasizes the importance of managing the patient's stress response for faster recovery, given that the body reacts to surgical procedures even under anesthesia.

By integrating music as a form of therapy in surgical settings, this research may lay the groundwork for a significant shift in how healthcare providers approach the surgical experience. With potential implications for patient wellbeing and recovery, the study highlights the profound interplay between cultural practices, such as music, and medical science.

This novel approach brings attention to music therapy, which has long been known for its benefits in psychology and rehabilitation, revealing how simple interventions can foster a more humane surgical environment. If music can promote healing as indicated by the results, it stands to transform future practices in hospitals, allowing the soothing power of melody to play a crucial role in patient care.

The study showed that when patients listened to calming instrumental music during laparoscopic cholecystectomy procedures, they required less propofol and fentanyl compared to those who did not receive musical treatment. Not only did this facilitate a faster return to consciousness, but it also contributed to lower stress hormone levels during surgery, enabling a smoother recovery process.

Dr. Farah Husain, a senior anaesthesia specialist involved in the research, emphasizes the importance of managing the patient's stress response for faster recovery, given that the body reacts to surgical procedures even under anesthesia.

By integrating music as a form of therapy in surgical settings, this research may lay the groundwork for a significant shift in how healthcare providers approach the surgical experience. With potential implications for patient wellbeing and recovery, the study highlights the profound interplay between cultural practices, such as music, and medical science.

This novel approach brings attention to music therapy, which has long been known for its benefits in psychology and rehabilitation, revealing how simple interventions can foster a more humane surgical environment. If music can promote healing as indicated by the results, it stands to transform future practices in hospitals, allowing the soothing power of melody to play a crucial role in patient care.