The timing of the first of several recent anti-gentrification protests in Mexico City was no coincidence - 4 July, US Independence Day.

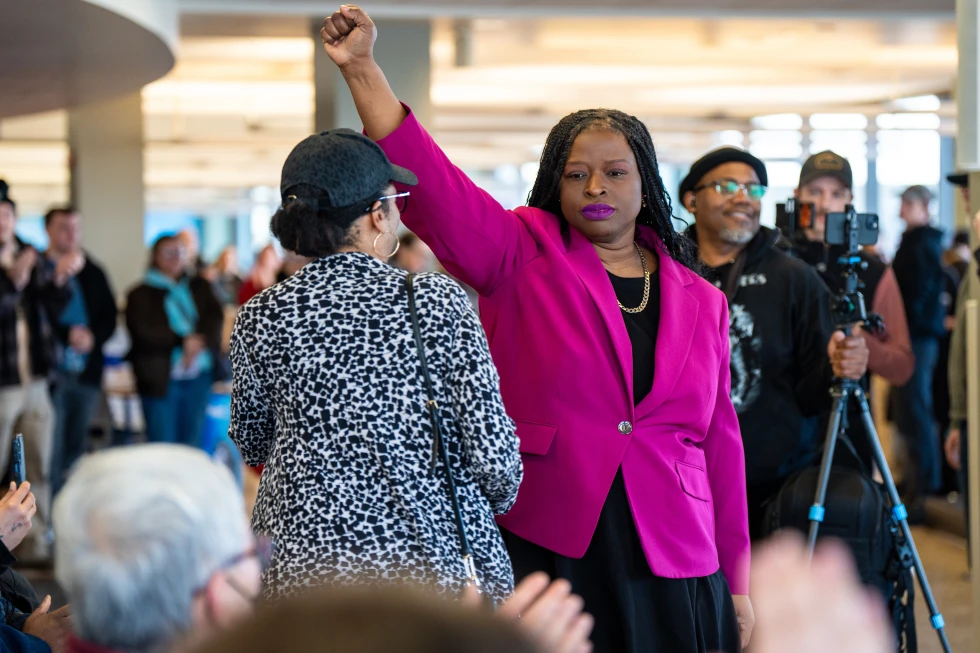

Demonstrators gathered in Parque México in Condesa district – the epicenter of gentrification in the Mexican capital – to protest over a range of grievances.

Most were angry at exorbitant rent hikes, unregulated holiday lettings, and the endless influx of Americans and Europeans into the city's trendy neighborhoods like Condesa, Roma, and La Juárez, forcing out long-term residents.

In Condesa alone, estimates suggest that as many as one in five homes is now a short-term let or a tourist dwelling.

Others also cited more prosaic changes, like restaurant menus in English, or milder hot sauces at the taco stands to cater for sensitive foreign palates.

But as it moved through the gentrified streets, the initially peaceful protest turned ugly.

Radical demonstrators attacked coffee shops and boutique stores aimed at tourists, smashing windows, intimidating customers, spraying graffiti, and chanting Fuera Gringo!, meaning Gringos Out!.

At her next daily press conference, President Claudia Sheinbaum condemned the violence as xenophobic. No matter how legitimate the cause, as is the case with gentrification, the demand cannot be to simply say 'Get out!' to people of other nationalities inside our country, she said.

Masked radicals and agitators aside, though, the motivation for most people who turned out on 4 July was stories like Erika Aguilar's.

After more than 45 years of her family renting the same Mexico City apartment, the beginning of the end came with a knock at the door in 2017.

Long-term residents of the Prim Building, a 1920s architectural gem located in La Juárez district, were visited by officials clutching eviction papers.

Erika recalls the shocking news: They came to every apartment in the building and told us we had until the end of the month to vacate the premises, as they weren't going to renew our rental contracts. You can imagine my mother's face. She's lived here since 1977.

The owners were selling to a real estate company, giving the residents a final offer of 53m pesos ($2.9m; £2.1m) to keep their home, an amount Erika describes as unrealistic.

Today, her old apartment is being transformed into luxurious rentals, designed for short stays in dollars, an arrangement that has left her reflecting on the loss of community.

It's not a construction for people like me, she laments, as she now lives almost two hours away from her old neighborhood.

Activist Sergio González mentions that his group has recorded over 4,000 cases of forced displacement from La Juárez in the past decade, emphasizing that the urban conflict is about who has the right to reside in the city.

Although Mayor Claudia Brugada offered a plan to tackle the housing crisis, critics argue it comes too late amidst a backdrop of rising rents and gentrification fueled by foreign investments.

As the protests highlight the ongoing struggle between local residents and the forces of gentrification, many are calling for a reconsideration of urban policies and efforts to protect the essence of Mexico City's neighborhoods.