Cape Town, South Africa - As fears of escalating crime and gang violence grip the townships surrounding Cape Town, many parents are confronted with an agonizing choice: send their children to danger-prone local schools or undertake grueling daily commutes to former white-only institutions. In Khayelitsha, Cape Town’s largest township, mother Sibahle Mbasana shares harrowing accounts of her sons witnessing violent incidents at their previous school, prompting her to seek safer educational environments for her children.

With roots in the painful legacy of apartheid, where the Bantu Education Act of 1953 established gross inequalities in schooling resources, the effects are still deeply felt. The barriers created by decades of systemic oppression are reflected in today's overcrowded township schools, with subpar facilities and rampant crime, forcing parents like Mbasana to reconsider their children's educational futures.

Mbasana, now 34, moved to Khayelitsha as a teenager and has opted to transfer her sons, 12-year-old Lifalethu and 11-year-old Anele, to a state school located 40 kilometers away in Simon's Town. Here, the family hopes for better class sizes and facilities, while also integrating their 7-year-old daughter, Buhle, into the safer school environment. However, the long commutes come with their own challenges.

"My children wake up at 4:30 a.m. and often return home exhausted after 4:30 p.m.," Mbasana describes. This routine not only drains their energy but also threatens their well-being, as recent incidents highlight the ever-present perils of public transport in their journeys.

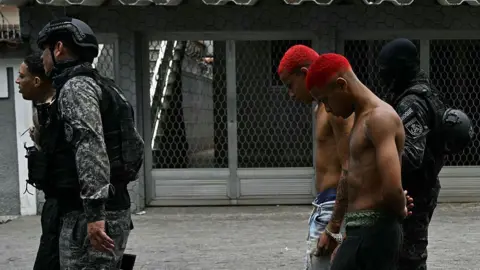

The stark reality remains: township schools may have commendable leadership and dedicated educators, but issues of safety loom large, with teachers at several institutions facing extortion from gangs. Reports reveal that some educators are coerced into paying gangs, creating a climate of instability in a system already beleaguered by sheer neglect.

As a broader picture emerges, one thing becomes clear—parents in underprivileged areas are hungering for change. They hope for equitable educational opportunities, akin to their more affluent counterparts, yet face insurmountable obstacles. Amidst budget cuts impacting teacher numbers and resources in township schools, many families feel abandoned in favor of wealthier institutions.

Efforts from the Western Cape Education Department to intervene by hiring private security and increasing police presence seem insufficient. Lives at stake have prompted parents to take desperate measures, hoping to pave a safer, more promising path for their children while navigating the chaos of poverty and systemic neglect.

As Sibahle Mbasana grips the reality of her family's precarious situation, she contemplates a future where safety is not a luxury but a right, as she and others silently plead for an equitable education system where every child thrives regardless of background or geography.