India's population just surpassed 1.45 billion, making it the world's most populated country. Paradoxically, this demographic milestone has sparked debates on expanding family sizes, particularly in southern regions. Leaders in Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu are urging policies to incentivize more births due to declining fertility rates and an ageing population, countering the long-standing trend of family planning and population control.

Andhra Pradesh has recently abandoned its "two-child policy" for local elections, while Tamil Nadu is exploring similar initiatives. Although India’s fertility rate has decreased from 5.7 births per woman in 1950 to two births today, concerns loom that southern states—having successfully maintained replacement-level fertility—may suffer politically and financially due to these changes.

The demographic landscape in southern India paints a worrying picture; states like Kerala and Tamil Nadu are grappling with low birth rates of 1.4 and 1.6, respectively, compared to several European nations. The potential reshaping of electoral boundaries for the first time since 1976, scheduled for 2026, is set to intensify fears that populous northern states may gain seats, further marginalizing the economically prosperous southern states.

Demographers and community leaders express concern about India's rapid shift towards an older demographic, predicting that it will reach high ageing rates much faster than countries like France and Sweden, which took centuries to increase their elderly populations significantly. The rapid decline in fertility is attributed to effective family planning programs, but this has left states struggling. With more than 40% of the elderly living below the poverty line, the question arises: can these regions sustain increased demands for pension and healthcare systems?

Experts highlight that fewer children mean a growing dependency ratio, leading to financial strain as there are fewer caregivers for an expanding elderly population. The ongoing trend of urbanization and migration only aggravates traditional family structures, further complicating support systems for older individuals.

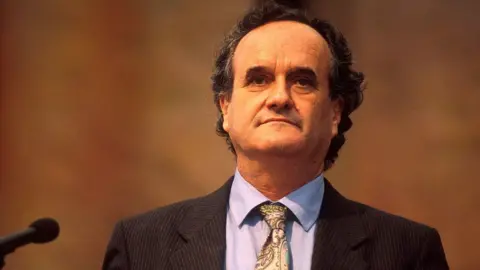

Adding to this multifaceted challenge, Mohan Bhagwat, head of the Hindu nationalist Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, has openly urged couples to have at least three children to secure the nation’s future, suggesting that a fertility rate below 2.1 could threaten societal sustainability. However, demographic experts caution against such claims, suggesting that encouraging higher birth rates often misses the root socio-economic factors influencing family planning decisions.

Countries like South Korea and Greece have already faced national emergencies due to declining birth rates, prompting drastic administrative responses. India is urged to focus on extending working-age lifespans and promoting healthier ageing to mitigate the demographic impact.

With the potential for economic growth tied to a large working-aged population, experts emphasize the need for India to optimize its demographic dividend before it becomes an unfavourable demographic balance. Policies that encourage better health screenings, higher retirement ages, and improvement in social security must become priorities for India to navigate its ageing crisis and capitalize on its remaining opportunities before the window closes in 2047.