At a time when women's participation in the film industry was frowned upon, a young woman dared to dream differently. In the 1920s pre-independence India, PK Rosy became the first female lead in Malayalam-language cinema, starring in a movie called Vigathakumaran, or The Lost Child. Yet instead of being remembered as a pioneer, her story was buried due to caste discrimination and social backlash.

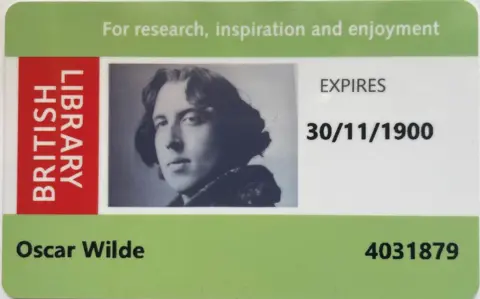

Rosy belonged to a lower-caste community and faced intense criticism for portraying an upper-caste woman. Almost a hundred years later, no evidence of Rosy's role survives; the film's reel was destroyed and the cast and crew have all died. The only remnants are a few pictures from a contested press release in 1930 and an unverified black-and-white photo circulated by local newspapers. A recent Google Doodle celebrating her 120th birthday used an illustration based on a photograph that may not even be her.

Born Rajamma in the early 1900s in Travancore, now Kerala, she hailed from a family of grass cutters within the Pulaya community, a Dalit group historically oppressed in India's caste hierarchy. Malavika Binny, a history professor at Kannur University, notes that the Pulaya community was subjected to severe discrimination and violence. Despite these challenges, Rosy dreamed of a different life, encouraged by her uncle, a theatre artist.

Rosy gained popularity in local theatre, which caught the attention of filmmaker JC Daniel, who cast her as the lead in Vigathakumaran, paying her a substantial five rupees a day. However, on the premiere day, she and her family were barred from attending due to their Dalit status. Following the screening, anger erupted in the audience over Rosy's role as an upper-caste woman, leading to violence against Daniel and ending any hopes for future productions.

Burdened by debt, Daniel never made another film, and Rosy fled her hometown after a vengeful mob destroyed her house. She was left with no choice but to marry an upper-caste man and adopt a new identity, Rajammal, effectively disappearing from the public eye. Furthermore, her children distanced themselves from her Dalit roots, living under the upper-caste identity of their father.

Years later, in 2013, a Malayalam TV channel tracked down Rosy's daughter Padma, living in financial strain, who claimed ignorance about her mother’s acting past. Attempts by the BBC to connect with Rosy's family were met with resistance, highlighting the stigma still surrounding her legacy. Binny suggests that Rosy's erasure illustrates the profound impact of caste-based trauma that shapes one's existence, although she eventually found safety.

Nonetheless, the legacy of PK Rosy is being reclaimed by modern Dalit filmmakers and activists, including Tamil director Pa Ranjith, who has initiated a yearly film festival in her honor. Despite progress, her story remains a poignant reminder of the sacrifice of art for survival, underscoring the lasting consequences of societal constraints on identity. “It’s not her failure – it’s society’s,” states Rosy’s nephew, reflecting on the heavy price paid for survival.