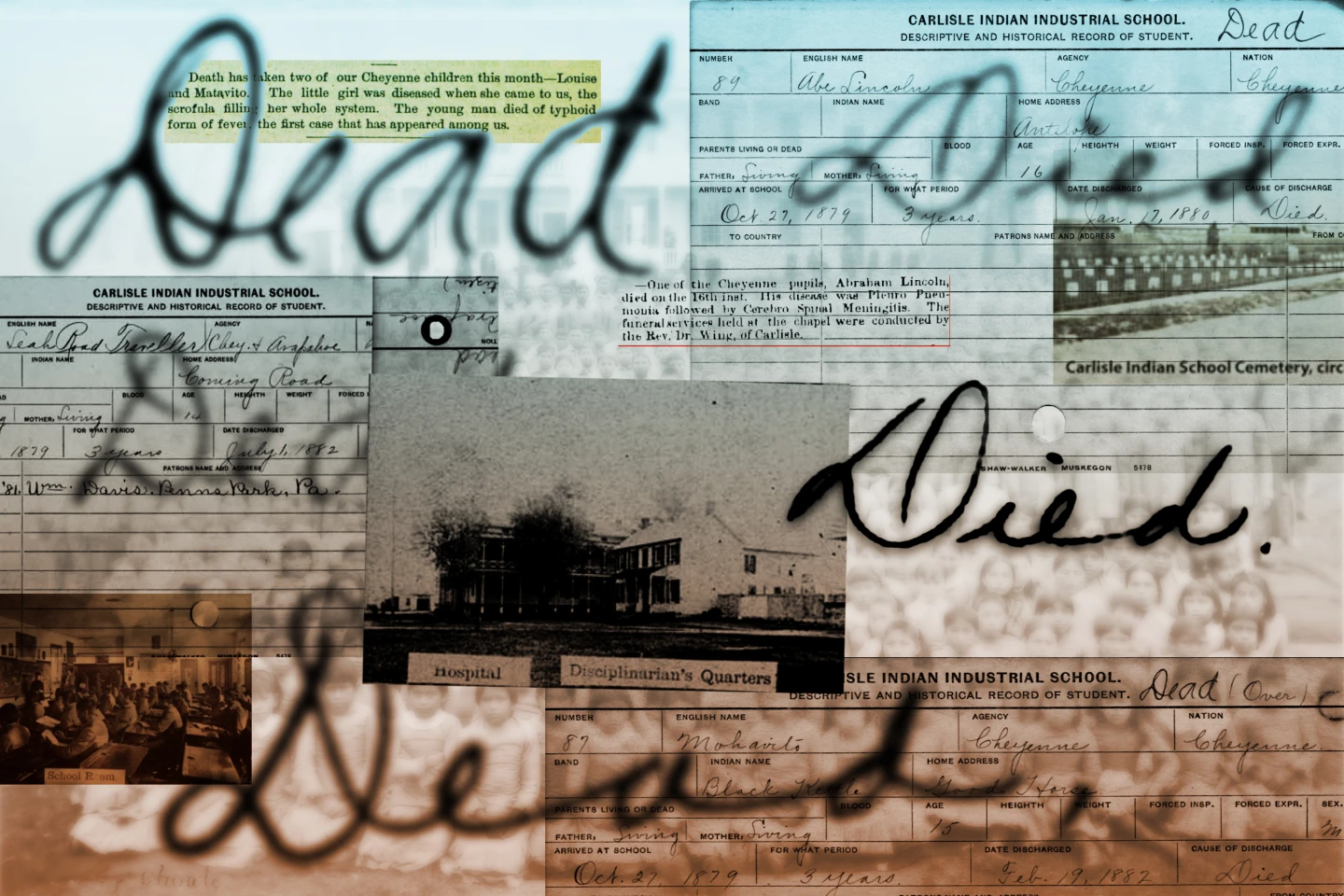

The South Korean Truth and Reconciliation Commission has released a damning report detailing the country’s history of "mass exportation" of children for adoption, revealing significant human rights violations that affected at least 170,000 children since the 1950s. The commission, which commenced its inquiry in 2022, uncovered a lack of oversight from the government, allowing private agencies to profit from children’s adoptions amid rampant fraud and coercion.

During a press conference, commission chairperson Park Sun-young described the findings as a "shameful part of our history," highlighting that while some adoptees found loving homes, many endured trauma throughout their lives due to flawed and exploitative adoption processes. Testimonies from affected individuals featured prominently, with one woman declaring that her adoptive parents "took better care of the dog than they ever did of me".

The independent report outlines how South Korea has historically adopted out more children than any other nation, primarily to Western countries. Even though the South Korean government has initiated reforms to its adoption practices, birth parents and adoptees continue to grapple with the legacy of exploitation. Since the inquiry's inception, 367 adoptees submitted petitions claiming fraud in their adoption processes, with 56 recognized as victims of human rights violations.

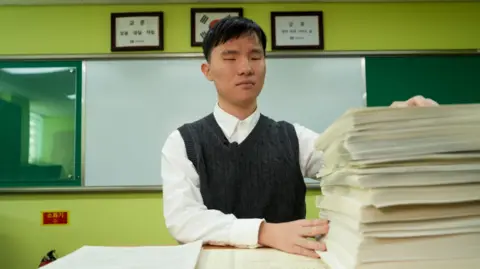

Adoption practices were largely left unregulated post-Korean War, fueled by substantial demand from foreign agencies. The report highlights that these agencies pressured Korean counterparts to supply a set number of children each month, leading to a system driven more by profit than by compassion. Reports of fabrications indicated children were falsely documented as abandoned, which complicated adoptees' ability to trace their origins and led to inadequate legal protections.

As a result of this inquiry, the commission has advised the government to issue a formal apology and align its adoption policies with international standards. Efforts to reform South Korean adoption law have already begun, with new regulations requiring that all overseas adoptions must be managed by a government ministry rather than private agencies by mid-2023.

Among the petitioners was Inger-Tone Ueland Shin, adopted by a Norwegian couple under dubious circumstances. She later discovered her adoption was illegal and recounted the feelings of isolation and pain stemming from her upbringing. Despite receiving a government settlement for damages in Norway, Shin lamented the lack of accountability for her past, calling for an end to international adoptions from Korea due to the associated suffering.

As the Truth and Reconciliation Commission continues to investigate additional cases, the urgency for South Korea to reconcile its adoption history is clearer than ever, as voices of adoptees demand recognition and healing from their painful past.