The last time Soe Ko Ko Naing saw his great-uncle was in July, at his home beside the Irrawaddy River. A labor rights activist and supporter of Myanmar's resistance against the military junta, Ko Naing had planned to flee to Thailand, a decision he confided to his beloved uncle. "I told him I was going to Thailand. He thought it was a good plan. He wished me good health and safety," he recalled.

Nearly a year later, Ko Naing is secure in Thailand, but his great-uncle was tragically killed in a devastating earthquake that struck near Mandalay last Friday, claiming more than 2,000 lives. "I have sleepless nights. I'm still suffering," Ko Naing expressed, battling a mix of guilt and helplessness. "I feel guilty because our people need us the most now."

Ko Naing represents millions in Myanmar's diaspora who anxiously watch their homeland struggle following its worst earthquake in a century. Many share his feelings of survivor's guilt, compounded by the reality that returning home could subject them to political persecution. Thailand is home to approximately 4.3 million Myanmar nationals, including a significant number of undocumented migrants.

The ongoing adversities following the 2021 military coup have only strengthened these communities, many of whom work in construction or agriculture. Sadly, many of the workers killed in the collapse of a Bangkok skyscraper due to the earthquake were believed to be from Myanmar.

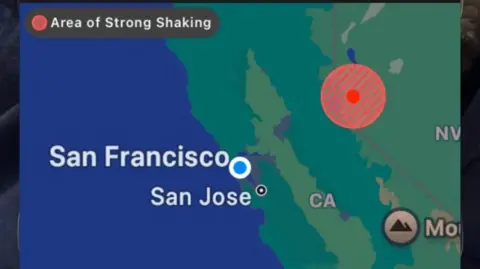

As Ko Naing navigates his life in Samut Sakhon, a fishing port near Bangkok, he finds it challenging to quell his anxiety over the situation back home. The echoes of the earthquake were felt far beyond Myanmar's borders, with tremors felt in Thailand, India, and China. "I felt the room shake for about 30 seconds," he said, recalling that day.

With slow communication following the quake, Ko Naing learned that most of his relatives in Sagaing were safe, except for a distant great-aunt and his valued Oo Oo. More than the loss, Ko Naing felt particularly crushed over how the earthquake had toppled the monastery where his uncle had sought refuge. "I was shocked and devastated... It was real," he reflected.

Their bond had deepened following the military coup. Sharing afternoons by the river, his uncle, who had suffered from a stroke, would still bring warmth and wisdom to their conversations. "He was my source of inspiration, especially in difficult times," Ko Naing remarked.

The journey to Thailand was fraught with peril, as Ko Naing and his family fled a regime that sought his arrest for protesting. They crossed into Thailand under the cover of darkness, where an encounter with border police turned nearly tragic. Yet, as they settled into their new life in Samut Sakhon, Ko Naing now faces depression from the compounded trauma of the pandemic, the ongoing military oppression, and the recent earthquake.

Despite his current struggles, he is actively working with the Myanmar diaspora community to provide humanitarian assistance for earthquake victims. "It's good that we're alive. We can still do something," he asserted. "We have to make up our mind on how to rebuild, how we can move on."