As helicopters circled overhead, sirens descended on her suburb, and people ran screaming down her street on 14 December, Mary felt a grim sense of deja vu.

That was when I knew there was something seriously wrong – again, she says, her eyes brimming with tears.

Mary - who did not want to give her real name - was at the Westfield Bondi Junction shopping centre in April last year when six people were stabbed to death by a man in psychosis, a tragedy still fresh in the minds of many.

Findings from a coroner's inquest into the incident were due to be delivered this week, but were delayed after two gunmen unleashed a hail of bullets on an event marking the start of the Jewish festival of Hanukkah eight days ago.

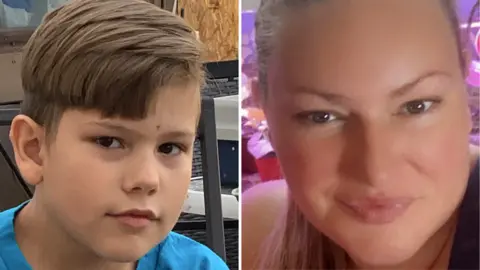

Declared a terror attack by police, 15 people were shot and killed, including a 10-year-old girl who still had face paint curling around her eyes.

The first paramedic to confront the bloody scenes at the Chanukah by the Sea event was also the first paramedic on the scene at the Westfield stabbings.

You just wouldn't even fathom that something like this would happen, 31-year-old Mary, who is originally from the UK, tells the BBC. I say constantly to my family at home how safe it is here.

This was the overarching sentiment in the days following the shooting. This kind of thing, mass murder, just doesn't happen in Australia.

But it can and it has – twice, in the same community, within 18 months.

A sea of flowers left by shocked and grieving people at Bondi is being packed up. A national day of reflection is over. On Sunday night, Jewish Australians lit candles for the last time this Hannukah.

But the two tragedies have left scores physically scarred and traumatised, and the nation's sense of safety shattered.

'Everyone knows someone affected'

Bondi is Australia's most famous beach - a globally recognised symbol of its way of life.

It's also a quintessential slice of Australian community. There's a bit of everyone knows everyone - and that means everyone knows someone affected by the 14 December tragedy, mayor Will Nemesh told the BBC.

One of the first people I texted was [Rabbi] Eli Schlanger. And I said, 'I hope you're OK. Call me if you need anything', he said.

But the British-born father of five, also known as the Bondi Rabbi, was among the dead.

The first responders, police and paramedics, would have been working on members of their own community. Others had the task of having to treat the shooters who had taken aim at their colleagues.

[Westfield Bondi Junction] was horrendous, something we're certainly not used to. And then this again was massive, catastrophic injuries, Ryan Park, health minister for New South Wales, told the BBC.

They've seen things that are like you would see in a war zone… You don't get those images out of your head, Park added.

Mayor Nemesh fears this will forever be a stain on Bondi, and Australia.

If this can happen here at Bondi Beach, it really could happen anywhere… the impact has reverberated around Australia.

'Warnings ignored'

No one is feeling this more than the Jewish community, for whom Bondi has become a sanctuary.

I swam here every day for years on end, rain or shine. And this week… I couldn't get in the water. It didn't feel right. It felt sacrilegious in some way, Dr Zac Seidler, a local clinical psychologist and mental health advocate, told the BBC.

Many of the victims of the attack moved here over many decades for safety from persecution, including 87-year-old Holocaust survivor Alex Kleytman. Instead, his life was bookended by violent acts of antisemitic hate.

Dr Seidler has spent the past two years trying to convince his grandparents, who are also Holocaust survivors, to hold on to their faltering belief in the good of humanity.

[My grandmother] kept saying, 'These are the signs. I've seen this before'. And I just kept saying, 'Not in Australia, not here. You're safe', just trying to soothe her.

But now I kind of feel like the fool.

No community is a monolith, but one thing many Jewish Australians believe is that warnings about a rise of antisemitism in the months preceding this attack were ignored.

The year started with a spate of vandalism and arson incidents on Jewish marks in the suburbs surrounding Bondi. It has ended with mass murder targeting their community.

Community, anger and sadness

The shooting triggered a massive outpouring of support from around the nation.

When the news broke, many in the community rallied to help.

Lifeguards - volunteer and paid - put their lives on the line. Restaurants opened their doors and hid people in their store rooms, and locals ushered lost children into their apartments.

Even the New South Wales opposition leader Kellie Sloane - also the local state member - was at the scene, helping pack bullet wounds.

In the days after the shooting, thousands of ordinary Australians lined up - many for hours on end - to donate blood desperately needed to treat those injured.

Each day, a carpet of petals, handwritten notes, commemorative stones and candles grew out from the gates of the Bondi Pavilion.

Bee motifs - stickers, balloons, even pavement art - are all over the suburb, in remembrance of Matilda, the attack's youngest victim.

Surfers and swimmers on Friday paddled out beyond Bondi's iconic breaks to honour those who died.

A day later, surf lifesavers and lifeguards stood shoulder to shoulder on the beach in solidarity with the Jewish community.

But amid the platitudes, sadness and shock is calcifying into anger and tension.

Last year's Bondi Junction stabbings were devastating for the community - but a shared resolution united it.

Experts say the attacker, who had schizophrenia, was in psychosis at the time of the stabbings, and his family have previously said he was frustrated at being unable to find a girlfriend. The question of whether he targeted women will likely forever go unanswered. But clear failures in the mental health system have been identified.

Last month, families of the victims asked the coroner to refer the doctor who weaned him off medication with limited supervision to regulators for investigation, and they have also argued for a massive boost to mental health service funding.

But last Sunday's events raise more uncomfortable feelings and questions.

There is palpable fury at the government, over a perceived – and admitted – failure to do more to stop antisemitism. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has been booed during public appearances this week, and talking to people visiting the site of the attack in Bondi, it isn't uncommon to hear them demand his resignation.

Many people the BBC spoke to pointed to his government's decision to recognise Palestinian statehood, alongside countries including the UK and Canada, and regular protests in Australia by members of the pro-Palestinian movement, which though largely peaceful but have been peppered with antisemitic chants and placards.

The state of New South Wales - which has in recent years successively tightened protest rules - has already announced it will introduce more legislation cracking down on hateful chants and give police more powers to investigate demonstrators.

The federal government has promised similar.

The blame apportioned to these protests does not sit right with many, even some sections of the Jewish community.

We need to hold multiple truths, Dr Seidler says. We can be afraid, we can feel that there is deep antisemitic rhetoric going on in certain circles within Australia… while also understanding that there is a right of people in this country – especially Muslim Australians – to be concerned about what is taking place in Gaza.

We need to get better at finding that line and calling out when that line has been crossed.

With the anger, there is also fear: for the Jewish community of other attacks, for the Muslim community of retaliation for an act of terror they have loudly condemned.

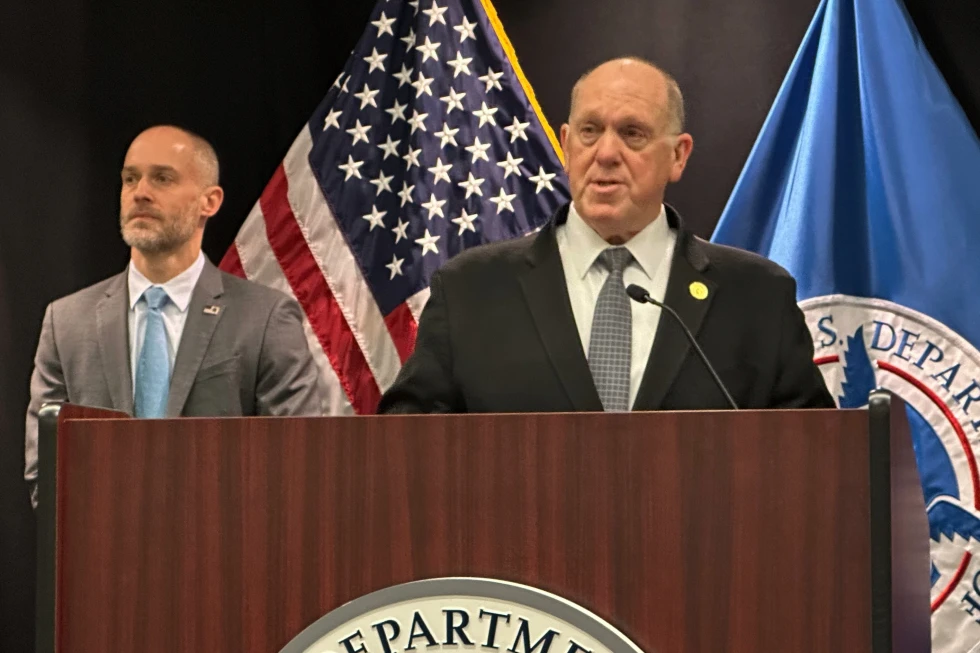

There are questions over how Australia's security agency came to drop a 2019 investigation into one of the alleged Bondi Beach suspects, prompting a review into federal police and intelligence agencies that was announced on Sunday.

There is frustration at NSW Police, who have for years been warned by the Muslim community of hate preachers poaching their young men.

There is animosity towards the media, driven by hurt among both Jewish and Arab Australians over a belief they have been misrepresented, and frustration at what some feel is incitement against them.

But there is also a queasiness at the treatment of traumatised victims throughout this week, some of whom were interviewed live on television while the blood of their friends still stained their hands.

Through it all, is an undercurrent of suspicion of institutions and each other.

There are varying opinions on how those rifts can heal – or even if they can. But there is a shared determination to try.