North Korea has long employed strategies to bolster its economy, particularly through the use of overseas labor. In a recent revelation, one defector, known only as Jin-su to protect his identity, shared insights into the clandestine practices of North Korean IT workers operating globally. His testimony exposes a multifaceted operation in which IT workers, many of whom are sent to various countries under false pretenses, work diligently to raise funds for the beleaguered regime.

Jin-su disclosed to the BBC that he and others engaged in this operation utilized fake identities to apply for remote IT positions in Western countries, typically earning a substantial monthly wage—approximately $5,000. He emphasized that even though it feels akin to "robbery," for many, it is a preferable existence compared to life in North Korea. Most of their earnings—estimated at 85%—are remitted back to the regime, highlighting the authoritarian state's reliance on these under-the-radar operations amidst ongoing international sanctions.

The clandestine nature of this enterprise is underscored by substantial reports from the UN Security Council, estimating that undercover IT workers generate between $250 million and $600 million annually for North Korea. The trend has surged during the pandemic as remote work became more mainstream, with many North Koreans reportedly employing strategies from utilizing borrowed identities to leveraging language skills to secure jobs with higher salaries, particularly from US firms.

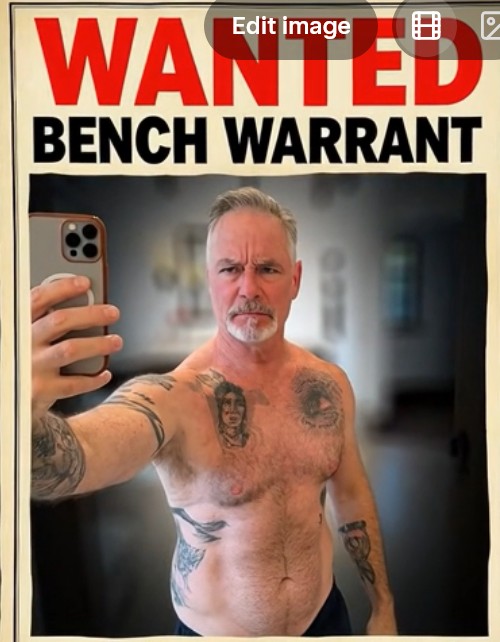

Jin-su recounted a routine of borrowing identities from Chinese and European citizens to facilitate his applications. "If you put an 'Asian face' on that profile, you'll never get a job," he explained, suggesting that deception is not just a practice, but a necessity in a world that steadfastly discriminates against applicants based on nationality.

Cybersecurity professionals are becoming increasingly vigilant as they encounter suspicious candidates during their hiring processes. Instances of North Korean workers slipping through the cracks have been reported, with hiring managers devising tactics—such as verifying daylight during video calls—to discern fraudulent applicants.

However, the plight of these workers is not without peril. The environment for defectors is fraught with dangers, as those who attempt to leave face grave consequences. Surveillance in China makes escape treacherous, and the social contract in North Korea often results in familial repercussions for defectors.

Despite having to leave behind a precarious but lucrative existence, Jin-su has found some solace in his new life. He continues to work in IT, albeit with higher integrity, recognizing that his decision to defect has allowed him to retain a greater share of his earnings compared to his previous endeavors for the regime.

"I had got used to making money by doing illegal things. But now I work hard and earn the money I deserve," he reflected, embodying the hope that one day, a future without oppression may exist not only for him but also for countless others still trapped within North Korea's rigid confines.

Jin-su disclosed to the BBC that he and others engaged in this operation utilized fake identities to apply for remote IT positions in Western countries, typically earning a substantial monthly wage—approximately $5,000. He emphasized that even though it feels akin to "robbery," for many, it is a preferable existence compared to life in North Korea. Most of their earnings—estimated at 85%—are remitted back to the regime, highlighting the authoritarian state's reliance on these under-the-radar operations amidst ongoing international sanctions.

The clandestine nature of this enterprise is underscored by substantial reports from the UN Security Council, estimating that undercover IT workers generate between $250 million and $600 million annually for North Korea. The trend has surged during the pandemic as remote work became more mainstream, with many North Koreans reportedly employing strategies from utilizing borrowed identities to leveraging language skills to secure jobs with higher salaries, particularly from US firms.

Jin-su recounted a routine of borrowing identities from Chinese and European citizens to facilitate his applications. "If you put an 'Asian face' on that profile, you'll never get a job," he explained, suggesting that deception is not just a practice, but a necessity in a world that steadfastly discriminates against applicants based on nationality.

Cybersecurity professionals are becoming increasingly vigilant as they encounter suspicious candidates during their hiring processes. Instances of North Korean workers slipping through the cracks have been reported, with hiring managers devising tactics—such as verifying daylight during video calls—to discern fraudulent applicants.

However, the plight of these workers is not without peril. The environment for defectors is fraught with dangers, as those who attempt to leave face grave consequences. Surveillance in China makes escape treacherous, and the social contract in North Korea often results in familial repercussions for defectors.

Despite having to leave behind a precarious but lucrative existence, Jin-su has found some solace in his new life. He continues to work in IT, albeit with higher integrity, recognizing that his decision to defect has allowed him to retain a greater share of his earnings compared to his previous endeavors for the regime.

"I had got used to making money by doing illegal things. But now I work hard and earn the money I deserve," he reflected, embodying the hope that one day, a future without oppression may exist not only for him but also for countless others still trapped within North Korea's rigid confines.