In the complex mosaic of the new Syria, the old battle against the group calling itself Islamic State (IS) continues in the Kurdish-controlled north-east. It's a conflict that has slipped from the headlines - with bigger wars elsewhere.

Kurdish counter-terrorism officials have told the BBC that IS cells in Syria are regrouping and increasing their attacks.

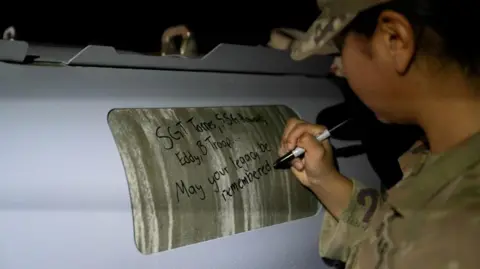

Walid Abdul-Basit Sheikh Mousa was obsessed with motorbikes and finally managed to buy one in January. The 21-year-old only had a few weeks to enjoy it. He was killed in February fighting against IS in north-eastern Syria.

Walid was so keen to take on the extremists that he ran away from home, aged 15, to join the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). His story is one among many as his family remembers him with affection amid the ongoing conflict.

His mother, Rojin Mohammed, recalls her son fondly, expressing her heartache as she calls for revenge against IS. They broke our hearts, she says.

According to Kurdish officials, the Islamic State has been taking advantage of the security vacuum following the ousting of Bashar al-Assad. There has reportedly been a ten-fold increase in their attacks, showing that IS is regrouping.

Jails Overrun with Detainees

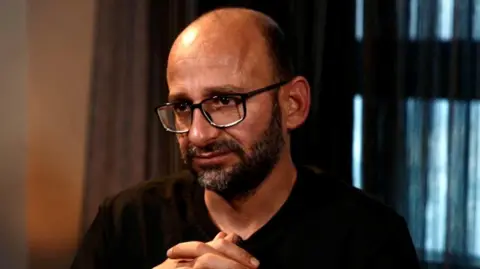

Kurdish authorities are grappling with the overwhelming number of suspected IS fighters held in their prisons, with around 8,000 detainees from 48 countries, including the UK and US. Many have remained untried and unconvicted for years, complicating the justice and security landscape.

The largest jail for IS suspects, Al-Sina in the city of Al Hasakah, has become emblematic of these issues. Detainees languish in conditions lacking basic amenities, facing a prison system that struggles to prevent the radicalization within its walls.

Some prisoners still wield influence, with reports of internal structures resembling the organization’s principles, raising alarms about the potential for further threats.

The Families Left Behind

Alongside the detainees, the social fallout of the conflict is observable within tented camps housing the families of suspected IS fighters, like the Roj camp in the Syrian desert. Women have shared their struggles, like Mehak Aslam, who lost her daughter in an explosion and has since grappled with the harsh realities of camp life while facing accusations of having participated in IS activities.

The survival and future of many children in these camps seem grim as they grow up surrounded by remnants of extremism, leading advocates to fear they may become the next generation of radicals.

“We are worried about the children,” says camp manager Hekmiya Ibrahim. “They are the seeds for a new version of IS, even more powerful than the previous one.”